Christopher A. Ferrara

REMNANT COLUMNIST, Virginia

Patrick Coffin, Street Magician and Catholic Answers' Hammer of Traditionalists

Since the close of the Second Vatican Council the Catholic Church has experienced the greatest crisis of faith and discipline in her history, caused by the spread of what Msgr. Guido Pozzo, Secretary of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei,

has described as “a para-Conciliar ideology … that substantially proposes once more the idea of Modernism.” By Modernism is meant the “synthesis of all heresies,” as Saint Pius X called it, a system of errors that greatest of Popes fought mightily to suppress because it undermines every aspect of doctrine and praxis it infects, proceeding by artful ambiguity in theology, demands for the “reform” and “updating” of the Church, and the “simplification” of her divine worship.

In the midst of the post-conciliar neo-Modernist invasion of the Church, why did an organization that calls itself Catholic Answers devote two hours of expensive radio time on May 31 to a live talk show attacking, not Modernism, but “radical traditionalists”? Why did the hosts of this show, Tim Staples and Patrick Coffin, dwell on a few Catholic adherents of the Society of Saint Pius X who (allegedly) lost their faith, while ignoring the “silent apostasy” that plagues the entire Western world—and this a half-century after the Council that was supposed to have made the faith more accessible to the masses? Why have Staples and Coffin planned another two hours of traditionalist bashing on August 12? And why has Catholic Answers devoted not one minute of its live radio show to the grave threat a resurgent Modernism poses to the souls of Catholics, who continue to apostatize by the millions under its influence? The answer to these questions, in a word, is this: neo-Catholicism, a kind of well-mannered second cousin to Modernism. Inveterate Remnant readers will know what I mean by the term, but for newcomers to this controversy a bit of background is in order.

What is a Neo-Catholic?

In The Great Façade (Remnant Press: 2002), my co-author and I introduced the term “neo-Catholic” to signify a constituency quite unknown in the Catholic Church before Vatican II. The term suggests a parallel to the “neo-conservative” of politics, whose “conservatism” involves the conservation of a liberalized status quo that is actually an ever-widening break with the “paleo-conservatism” (traditionalism) of the past. In a manner akin to neo-conservatives who look down their noses at paleo-conservatives, neo-Catholics disdain Roman Catholic traditionalists because they have continued to be what neo-Catholics themselves once were, and what all their ancestors were for centuries before—that is, Catholics who believe and practice the unreconstructed faith of their fathers from the liturgy, to the catechism, to the rites of the sacraments.

Since the Council we have witnessed, for the first time in the Church’s bimillenial history, the emergence of a strain of Catholic “neo-conservatism”—hence neo-Catholicism—characterized by a staunch defense of unprecedented ecclesial novelties the Popes before the Council would have viewed with utter horror. Among other novelties comprising the liberalized ecclesial status quo of the post-conciliar epoch, the neo-Catholic defends the new vernacular liturgy (including the appalling spectacle of altar girls, approved by “John Paul the Great”), the new “ecumenism,” which has all but de-missionized the Church, and the new “dialogue,” which has reduced the perennial preaching of the Gospel with the authority of Christ Himself to a vacuous “discussion-ism” that avoids any open proclamation of the imperatives of divine revelation, especially the claims of Christ on nations as well as individuals.

Concerning “dialogue,” as Romano Amerio observed in his masterwork Iota Unum, this “is very new in the Catholic Church…” The word “was completely unknown in the Church’s teaching before the Council. It does not occur once in any previous council, or in papal encyclicals, or in sermons or in pastoral practice.” Yet this novelty suddenly appears 28 times in the Vatican II documents that were drafted in haste after the classically written preparatory schema, years in the making, were tossed into the trash following the famous Rhine group uprising on the Council’s third day. (Cfr. Wiltgen’s The Rhine Flows into the Tiber, pp. 15-60). Amerio notes that dialogue, “through its lightning spread and an enormous broadening of meaning, became the master-word determining post-conciliar thinking, and a catch-all category in the newfangled mentality.” (Iota Unum, p. 347). The newfangled mentality to which Amerio refers is the mentality fairly described as neo-Catholic.

The unprecedented emergence of a liberalized neo-Catholicism as the purported mainstream of the Church after the Council has given rise to a correlative and equally unprecedented development: ghettoization of the Catholics now called traditionalists, who declined to embrace ecclesial innovations introduced in the Sixties and Seventies, which were never imposed as binding matters of faith and morals in the first place. (No Catholic, for example, has ever been obliged to attend the New Mass or to participate in “ecumenical prayer meetings,” much less the bizarre inter-religious spectacles of which John Paul “the Great” was so fond.)

This unparalleled sweeping liberalization of the Church in the name of Vatican II—all in the vain hope of making her doctrine and worship more appealing to “the modern world”—has, of course, come to ruin. Former Pope Benedict, who made significant efforts to reverse the debacle, laid all reasonable debate on that score to rest during the final days of his all-too-brief pontificate. In his address to members of the Roman Curia he blamed a “virtual Council” and a “Council of the media” for what happened: “so many disasters, so many problems, so much suffering: seminaries closed, convents closed, the liturgy banalized…”

And it was Benedict who, writing as Cardinal Ratzinger, made this astonishing observation about a situation the Church has never before encountered: “I am convinced that the ecclesial crisis in which we find ourselves today depends in great part upon the collapse of the liturgy, which at times is actually being conceived of etsi Deus non daretur [as if God were not a given]: as though in the liturgy it did not matter any more whether God exists and whether He speaks to us and listens to us. But if in the liturgy the communion of faith no longer appears, nor the universal unity of the Church and of her history, nor the mystery of the living Christ, where is it that the Church still appears in her spiritual substance?” (La Mia Vita, April 1997).

The neo-Catholic mind is not troubled by this catastrophe, much less determined to oppose the reckless innovations that caused it. The neo-Catholic attitude to what even Paul VI admitted was “a process of self-destruction” of the Church (Allocution of December 7, 1968) is essentially: “What’s the big deal?” I will let Mr. Coffin’s own words in defense of his first two-hour foray against “radical traditionalists” establish the point:

It happens to be easy to gripe about the many pressing problems facing the Church today, easy to be agog at the banality of many Ordinary Form (OF) liturgies with their clap-happy ditties that pass for sacred music, easy to lament the indisputable decline of Sunday Mass attendance since the early 1960s, and easy to be vexed by the pitiful state of catechesis in this country.

But let’s keep our eyes on the ball. The end is the life of glory with God in the beatific vision, not the Traditional Latin Mass, nor the Ordinary Form, no matter how reverently done. We need to love Jesus Christ and his Bride. On his terms, not ours.In two paragraphs of flippant prose, Coffin dismisses an almost apocalyptic collapse of faith and discipline in the Church. What does it matter, says he, that the liturgy has become banal, indeed a joke, that Mass attendance has declined, that catechesis is pitiful (not only in this country, by the way, but throughout the world)? What matters is that we attain the beatific vision—as if the very substance of the faith had nothing to do with reaching that goal!

In effect—and this is typical of neo-Catholic cant—Coffin implicitly dispenses with both orthodoxy and orthopraxis, reducing the doctrine and practice of the Faith to a zero-sum game in which, no matter what corruptions invade the Church through the negligence of the pastors and the influence of the Adversary, the salvation of souls will be unaffected. If the sainted Popes of the Holy Church’s long history had thought that way, the Church would never have been restored in times of crisis through vigorous reform, and Western civilization would have descended permanently into darkness after the fall of Rome during the age of Augustine.

Coffin’s attitude is something we might expect from a Lutheran, but not from a Catholic who loves the Church and grieves at the wounds that a reckless penchant for novelty has inflicted upon her these past fifty years. Even Paul VI grieved over what had happened to the Church in so short a time after the Council’s disastrous “opening to the world,” but present-day neo-Catholic commentators like Coffin, confronted with the evidence of a half-century of what Pope Paul called “a veritable invasion of the Church by worldly thinking,” see no cause for grief. Rather, they busy themselves attacking traditional Catholics for standing up in opposition to the auto-demolition of the Church.

Neo-Catholic Chestnuts

The cargo of neo-Catholic chestnuts Coffin and Staples unloaded during their May 31 broadcast has already been very ably addressed by Peter Crenshaw in his two-part Remnant article. I add here only a few observations.

Stung by the audience backlash, Coffin and Staples were quick to retort that their target was not traditionalists as such, but rather “radical traditionalists.” In an article defending the broadcast and promising another, Coffin

was at pains to declare that he and Staples were not speaking of “‘Traditional Catholics’ who exhibit often heroic public witness to the Faith: that merry band of Latin-Mass-going, chapel veil-donning, homeschooling, nightly rosary-praying, great books-loving Catholics. In the courage of their faith and willingness to share it, these salt-of-the-earth Catholics deserve emulation.”

A telling remark indeed. For if Coffin and Staples really believe this, why are they themselves not “traditional Catholics”? Notice, rather, that they implicitly distinguish themselves from “traditional Catholics.” That is because they are not traditional Catholics, and they know it. They are precisely what I am suggesting here: neo-Catholics—again, something the Church never saw before Vatican II, when all Catholics were traditional Catholics.

But no sooner does Coffin praise “traditional Catholics” then he damns them under another title. While admitting that they “are not Rad-Trads outside the Church” he avers that “they’re Mad-Trads inside the Church.” And what is a “Mad-Trad”? Essentially, it is any Catholic who objects to the post-conciliar status quo of widespread apostasy, liturgical degradation, and theological revisionism to which the neo-Catholic has quietly accommodated himself in the smug certitude that none of it really matters anyway.

Coffin caricatures the traditionalist position as “strident resistance to the Second Vatican Council and all its pomps and all its works,” when he has to know that the real issue is the Council’s vexing ambiguity in “pastoral” texts unlike those of any other Council, texts which require a “hermeneutic of continuity” that is itself an indictment of the Council’s failure of clarity. As even the arch-Modernist Cardinal Walter Kasper

recently admitted on the very pages of L’Osservatore Romano, in the Council texts are “compromise formulas, in which, often, the positions of the majority are located immediately next to those of the minority, designed to delimit them. Thus, the conciliar texts themselves have a huge potential for conflict, open the door to a selective reception in either direction.” Like neo-Catholics generally, Coffin refuses to acknowledge the Council’s unique problematicity, reducing legitimate concerns over the problem to “resisting Vatican II,” as if the Council were a kind of ecclesiastical wave function to which Catholics must attune themselves, mindlessly vibrating in the proper frequency.

Coffin sniffs that the “Catholic charismatic renewal is frequently singled out for tarring and feathering, despite (or because of?) strong papal support of that movement since the late ‘60s.” Evidently, Coffin sees nothing amiss with mass gatherings of deluded people who think they can turn the Holy Spirit on like a water faucet, babble nonsense they insist is the readily available “gift of tongues,” worship to the accompaniment of rock music, and treat the Holy Eucharist like portions of a personal pan pizza distributed by the unconsecrated hands of lay people. The “strong papal support” for this imaginary “renewal” of Protestant origin—which the Church condemned before the ill-starred Sixties to which Coffin refers—has never found its way into a binding papal pronouncement on faith and morals. Rather, it belongs to the category of things the conciliar Popes have improvidently tolerated or praised informally. But then, Paul VI praised his New Mass to the heavens, only to lament the almost immediate liturgical disintegration its introduction provoked. (Too late did he sack Bugnini, packing him off to Iran and shutting down his Congregation after reading what Bugnini himself admits was a dossier on his alleged Masonic affiliations.)

Coffin refers to the “Mad-Trad’s” supposed penchant for “conspiracy theories involving Jews and Masons.” By this he means the more than two hundred papal condemnations of Freemasonry including, yes, warnings about Masonic plotting against the Church—foolish “Mad-Trad” Popes!—and the Church’s traditional teaching on the fundamental opposition between the Christophobic teaching of the Talmud and the truths of the Gospel, prompting Mad-Trad pre-conciliar Popes to place the Talmud on the Index of Forbidden books and order its destruction.

Then there is the obligatory neo-Catholic revision of the Message of Fatima. Coffin writes that “Mad-Trads tend invariably to reject the position of the Catholic Church regarding the 1984 consecration to Russia by Blessed Pope John Paul II as requested in 1917 by our Lady of Fatima. In the face of repeated affirmations by the Holy See to the contrary, Mad-Trads say that consecration didn’t ‘take’ because her request was not fulfilled.”

If Coffin knew anything about the subject, he would know that the Catholic Church has never taken a position on whether John Paul’s consecration of the world in 1984 was a consecration of Russia. John Paul himself never said as much, and we know from the revelations Bishop Paul Josef Cordes that while John Paul “thought, some time before [the Consecration], of mentioning Russia in the prayer of benediction… at the suggestion of his collaborators he abandoned the idea.” (Father Andrew Apostoli, Fatima for Today: the Urgent Marian Message of Hope, p. 251.)

In other words, John Paul II had the intention of fulfilling Our Lady of Fatima’s request, but his worldly-wise advisors talked him out of it. Thus traditionalists are at liberty to hold the audacious opinion that a consecration of Russia really needs to mention Russia, and that Russia could hardly have been consecrated to the Immaculate Heart in a ceremony from which any mention of Russia was deliberately omitted in order to avoid offending the Russian Orthodox, or provoking the Soviet leaders, or whatever other excuse was proffered by Vatican bureaucrats who think themselves more prudent than Virgo prudentissima.

As for the “repeated affirmations of the Holy See” to which Coffin refers, the term “Holy See” has steadily expanded to the point where it means any statement by any Vatican functionary—in this case, the assertions of Cardinal Bertone and Cardinal Sodano that Russia was consecrated without mention of Russia. But what competence does the Vatican Secretary of State have in the matter of Fatima? None whatever. And what Catholic with any sense would regard Cardinal Sodano—an ecclesiastical fixer who covered up the Father Maciel scandal for years until Cardinal Ratzinger reopened the investigation—as an authoritative interpreter of the Fatima event?

By the time Coffin is through disparaging “Mad-Trads” he has effectively equated them with the “traditional Catholics” he purports to admire. What, then, of the “radical traditionalists” Coffin and Staples claim were their real target? Predictably, they include in this category adherents of the Society of Saint Pius X, who, according to them, belong with “others on the ecclesial far right who have broken communion with the Roman pontiff for their own sundry reasons.”

The irony here is exquisite: In the midst of the worldwide silent apostasy that Coffin and Staples ignore, the Society—not one of whose clergy or laity is under any sentence of excommunication—represents one of the few groups in the Church today that have actually maintained communion with the Roman Pontiff by following all the teachings of the Popes and Councils on faith and morals, even if the Society’s canonical situation needs to be regularized. While straining at the gnat of the Society’s canonical status, Coffin and Staples—like neo-Catholics in general—swallow the camel of mass dissent by tens of millions of Catholics, and innumerable Modernist clergy, from infallible teachings of the Magisterium on everything from abortion, to contraception, to divorce, to women’s “ordination,” to “gay rights” and “gay marriage.” Yet Coffin has the gall to dismiss the Society’s faithful Catholics as nothing more than followers of “Extremely High Church Protestantism.” Meanwhile, the patent Protestantization of the vast majority of Catholics in the Western world escapes his ire.

But this double-standard is a salient trait of the neo-Catholic mind: no enemies to the left, be they Modernists in the hierarchy, legions of Catholics in the pew who reject Church teaching, squeaking and squawking charismatics, or such “conservative” orders as the Legionaries of Christ, that Latin Mass-averse religious order devoted to Vatican II, which neo-Catholic commentators doggedly defended (along with John Paul “the Great”) until the evidence of the vile corruption at its core became incontrovertible.

Here Coffin and Staples are guilty of calumny, plain and simple. This is shown by

a statement just issued by the Diocese of Richmond (where I now reside), retracting its own falsehoods concerning the Society in the diocesan newspaperCatholic Virginian. The Diocese had the decency to correct itself by admitting what Coffins and Staples mendaciously deny:

Our former Holy Father, Benedict XVI, never personally declared that doctrinal differences stand in the way of regularizing the canonical status of the society; nonetheless, the regularization has yet to take place….

The Masses offered by priests of the society are valid…

It is not clear that the society is in schism, and it is not properly called a ‘sect’….

…. In regard to the lay faithful who attend Mass at society chapels, there has never been a statement by the Holy See that these people are in schism. In fact, the Holy See acts toward them as it does toward all the Catholic lay faithful….

…[I]n the case of the society, the ministerial acts of their priests may be illicit and still be considered valid by the Church….

The Church’s unity is best served when the whole truth is communicated. We regret the errors in the article….Coffins and Staples are not interested in conveying the whole truth about the Society. Their aim is to condemn “radical traditionalists” while remaining silent about the neo-Modernists who have been busily demolishing the Church for nearly half a century without any serious opposition from the neo-Catholic constituency. In fact, the very existence of that constituency has vastly facilitated the Modernist resurgence after Vatican II.

Meet the Neo-Catholic Vulgarians

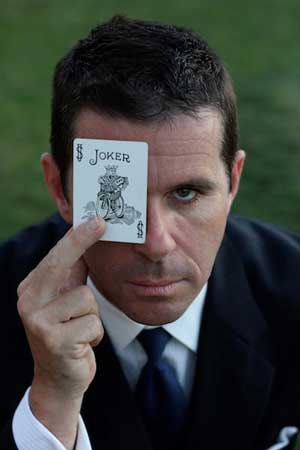

Coffin’s attempt to defend himself against the backlash he and Staples provoked with their first show prompted me to look a bit further into his background. I was not surprised to find that this former stage actor and currently practicing

street magician authored one of those works neo-Catholics delight in churning out: pop-theological discussion of the Church’s teaching on marriage and procreation, written in the smug confidence that crudely colloquial treatment of the most sensitive subjects by laymen will somehow make for a more compelling presentation of Church teaching than is to be found in those musty old theological manuals and arcane papal encyclicals.

In his book entitled Sex Au Naturel—how typical of the crass attempts at wit that characterize so much of neo-Catholic writing—Coffin informs us that “Catholic moral theology also uses technical language that can sometimes mislead. A good example is the word ‘evil,’ which conjures up images of red grinning devils brandishing pitchforks.” (Kindle Edition, location 259). For the neo-Catholic, evil is a technical term, and is even seen as faintly ridiculous. It never occurs to people like Coffin that belittling the concept of evil is symptomatic of a loss of faith, and it is precisely a recovery of the fear of evil as such that is one of the Church’s most urgent tasks today.

Coffin’s book announces yet another neo-Catholic novelty: what he calls “the NFP lifestyle.” Since when did the practice of “natural family planning” become a lifestyle? Since the neo-Catholic establishment got hold of it. As Coffin would have it, recourse to the infertile cycles is not something to which a couple may resort for a grave reason, but rather is a veritable way of life. He writes: “Couples who use NFP must have an all-important conversation each month. Will we have another baby?” (Kindle location 2690).

They must? Every month? What Pope or Council ever taught such a thing? When, before Vatican II, did Catholic spouses ever live that way? Never, of course. Coffin and his fellow neo-Catholics have simply invented this new teaching, and they extol it with disgusting abandon. “The main goal of this book,” Coffin writes, “is to shed light upon an issue notorious for its heat. The title Sex au Naturel conveys the essence of sexual communion in marriage that is free of chemical or mechanical encumbrances, ‘nakedly’ open to its twofold meanings of unity and procreation. In other words, organic sex. One hundred percent all natural ingredients. Safe for the environment of the body. Green sex, you could say, as encapsulated by the natural family planning lifestyle.” (Kindle locations 264-268).

We have had quite enough of this neo-Catholic degradation of the religion founded by Christ and preserved intact for two millennia by the majestic and infallible Magisterium of His Church, which has never needed to descend to cheap vulgarity in order to preach the Gospel. On the contrary, it has always been the exalted dignity of the Faith that has attracted souls and led them to heaven. The neo-Catholic vulgarians, whose popular works have multiplied since the Council, have not succeeded in making the Gospel more accessible by translating it into lowly contemporary patois. On the contrary, ordinary Catholics have never had less comprehension of the Gospel’s sublime teaching than today, after five decades of conciliar “renewal.”

Conclusion

Let us strain charity to the limit and allow that Coffin and Staples may have good intentions. Objectively speaking, however they ought to be ashamed of their demagogic grandstanding at the expense of fellow Catholics. Catholic Answers ought to terminate their campaign of calumniating “radical traditionalists” and “Mad-Trads,” who are merely victims of the ecclesial crisis, and direct its attention to the mass apostasy that afflicts the Church today, for which traditionalists bear no responsibility. Catholic Answers should begin that task of reparation with the two-hour show Coffin and Staples plan for August 12.

Finally, I know that there are people at Catholic Answers who find the antics of Coffin and Staples appalling and dearly wish that apostolate would embrace the cause of Tradition instead of what Michael Matt has called “cool Catholicism.” Our Nicodemus friends at Catholic Answers know that it is only the timeless Faith, and the ancient liturgy of apostolic origin that instantiates it, which can lead souls aright with absolute surety, not the time-bound novelties of the post-conciliar epoch, which were passé from the moment they first appeared. When the neo-Catholic establishment abandons its defense of novelty and joins traditionalists in seeking to recover what has been lost in the reigning diabolical confusion, the day of the Church’s emergence from the post-conciliar crisis will be near at hand. Until then, as Coffin and Staples have demonstrated, neo-Catholicism will remain a major impediment—perhaps the major impediment—to the immense task of restoring our devastated vineyard.