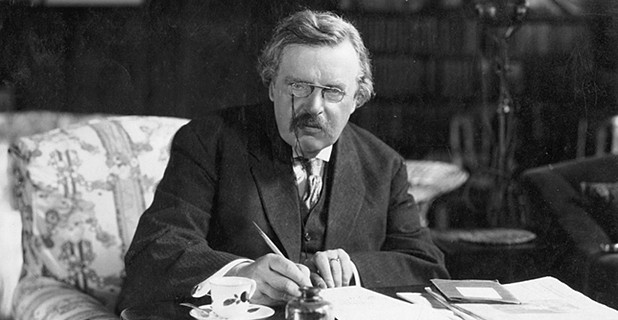

There was a great deal wrong with the world in 1905, so much so that G. K. Chesterton felt compelled to write a collection of essays titled aptly enough What’s Wrong With the World?Fans of Chesterton who have the good fortune to peruse this volume will likely experience repeated bouts of déjà vu as they recall the most recent headlines from around the globe. Although the Apostle of Common Sense would undoubtedly find plenty of things gone amiss in our world were he alive today, none, I am convinced, would he find as disconcerting as the trend among some religious orders and organizations to socialize the gospel. Among the worst offenders is the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), a group whose orthodoxy has become so questionable that the Vatican has intervened by requesting a doctrinal assessment of the organization.

So what would Chesterton find wrong with the LCWR?

In its quest to socialize the gospel, the LCWR has committed what Chesterton dubbed “the first great blunder of sociology,” which is “the habit of exhaustively describing a social sickness, and then propounding a social drug.” Hence, visitors to the LCWR’s Web site will find no shortage of articles calling for action on an array of socio-political issues ranging from clean energy to corporate corruption. Members of the LCWR are encouraged, among other things, to protect the earth’s fragile wetlands, to promote clean energy, to support the Occupy Wall Street movement, even to boycott Walmart because of the company’s association with sweatshop labor. Notably absent, however, are admonitions to proclaim repentance or to defend the life of the unborn or to protect the sanctity of marriage.

Now, I think Chesterton would have been more than happy to befriend the wetlands had he known they needed befriending; I also believe that, notwithstanding his fondness for cigars, he would have endorsed reasonable measures to promote clean and sustainable energy. What the Curmudgeon of Catholicism would have vehemently denounced, however, is the LCWR’s conflation of sin and sociology such that the gospel becomes essentially a clarion call to social action, and sin is redefined to encompass only those perceived injustices committed by the collectives in power. This is not the gospel Chesterton embraced, nor is it the gospel Christ entrusted to his apostles.

When St. Peter delivered his first sermon on the day of Pentecost, he preached neither to governments nor to corporations, but to individuals. “Repent,” he boldly proclaimed, “and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ…. For the promise is to you and to your children and to all that are far off, every one whom the Lord our God calls to him” (Acts 2:38-39). Peter’s message was intensely spiritual, focusing on the unique role of Christ in God’s plan of salvation. Absent is any mention of the oppressive taxation to which he and his audience were subjected. Absent is any reference to the brutal Roman occupation of the Palestinian land that he and his fellow Jews held dear. Absent is any talk of slavery or of war or of political corruption, all of which had reached proportions that would make the concerns of our current world pale in comparison. The slavery with which Peter was most concerned was slavery to sin. The corruption he and the other apostles cared about most was corruption of the heart.

The apostles had been entrusted with proclaiming the good news of salvation, and while they certainly were not indifferent to the socio-political turmoil around them and the human suffering it inevitably produced, they realized their great commission was not to reform society but to reconcile man with God. Once that occurred, society would reform itself.

In addition to being spiritual, St. Peter’s Pentecost sermon was both personal and familial in that it was directed to individuals and their offspring (“For the promise is to you and to your children…”). Addressed neither to empires nor to municipalities, the apostle’s message targeted that most humble of institutions—the family. As the Catechism reminds us, the family constitutes a singularly privileged unit of society, one that is rightly called a “domestic church” (2204). Sadly, however, proponents of the modern social gospel have neglected to honor this sacred institution, thereby undermining its importance as well as its utility, for indeed, as Chesterton lamented, “Socialists are specially engaged in mending (that is, strengthening and renewing) the state; [but] they are not specially engaged in strengthening and renewing the family.”

Unfortunately, judging from its public statements, the LCWR doesn’t appear to be all that concerned with directly strengthening and renewing the family either, except in a roundabout way, to the extent that a big government, a clean environment, a peaceful globe, and the demise of Walmart might lead to stronger families. To its credit, the LCWR has voiced support for a balanced immigration policy that would reunite the families of undocumented immigrants. Other than this commendable support, the LCWR has been notably silent in advocating the traditional family as a privileged community foundational to our larger society and essential to the preservation and transmission of the gospel.

According to its own statement of purpose, the LCWR’s Global Concerns Committee “initiates resolutions and activities that forward a social justice and peace agenda, especially on issues that impact women and children.” What, however, could the LCWR possibly believe to be more important for a child than to grow up in a stable family with both a mother and a father who have entered into a sacramental covenant and made Christ the head of their household? What social justice or peace agenda is served when our nation’s largest organization of women religious remains completely silent about the holocaust that has claimed the lives of tens of millions of unborn children and psychologically scarred an equal number of women?

Not only has the LCWR failed to advocate on behalf of the unborn, it has shown a reluctance even to acknowledge an unborn child’s absolute right to life. When asked in an NPR interview about the LCWR’s stance on abortion, Sister Pat Farrell, president of the conference, replied: “Our works are very much pro-life. We would question, however, any policy that is more pro-fetus than actually pro-life. If the rights of the unborn trump all of the rights of all of those who are already born, that is a distortion, too—if there’s such an emphasis on that.” I’m not sure exactly what that is supposed to mean, but as best I can tell, the import is this: We’re not really pro-life in the conventional sense of the term, but we oppose war and poverty, and we support universal healthcare, so in a reinvented sense we can call ourselves pro-life.

Herein lies another problem with the LCWR that Chesterton had the prescience to see more than a century ago: the tendency of modern Socialist groups to obfuscate language in a way that conceals their real agenda. As Chesterton remarks in a chapter titled “The New Hypocrite:” “It is not merely true that a creed unites men. Nay, a difference of creed unites men—so long as it is a clear difference. A boundary unites.” He then adds, “Our political vagueness divides men, it does not fuse them. Men will walk along the edge of a chasm in clear weather, but they will edge miles away from it in a fog. So a Tory can walk up to the very edge of Socialism, if he knows what is Socialism. But if he is told that Socialism is a spirit, a sublime atmosphere, a noble, indefinable tendency, why, then he keeps out of its way; and quite right too.”

Such gobbledygook resembles the sort of doublespeak that the LCWR routinely generates in an effort to question the magisterium while attempting to maintain a safe harbor from critics within the church who themselves question the group’s orthodoxy. Rather than risk an outright confrontation with the Vatican by questioning the church’s teaching on human sexuality, for example, the LCWR tells the public that “the teaching and interpretation of the faith can’t remain static and really needs to be reformulated, rethought in light of the world we live in.” And instead of forthrightly admitting that their obedience to the pope has limits, the group’s leadership tells us that they will continue discussions with Archbishop Sartain “as long as possible, but will reconsider if LCWR is forced to compromise the integrity of its mission.” Exactly how they believe the Vatican might compromise their integrity I am not sure. One thing seems clear, however, despite the opaque rhetoric: the LCWR is drawing a line in the sand (though precisely where that line is, it either doesn’t know or won’t say) and is letting it be known that it can be pushed around only so far (though just how far, it either doesn’t know or will not say).

As a man of unparalleled common sense, G. K. Chesterton valued honest, straightforward debate, regardless of how lively it might become. Moreover, as one who regarded dogma as man’s chief intellectual pursuit, he was willing to show respect even for the opinion of his most vociferous opponent—provided, that is, his opponent was straightforward and equally dogmatic. “I am quite ready,” Chesterton said, “to respect another man’s faith; but it is too much to ask that I should respect his doubt, his worldly hesitations and fictions, his political bargain and make-believe.”

Those controlling the LCWR apparently have doubts about the faith of the church and, in as much as they sincerely believe that saving the wetlands and occupying Wall Street are authentic expressions of the gospel, have inadvertently fallen victim to their own game of pretend. Chesterton once said, “I owe my success to having listened respectfully to the very best advice, and then going away and doing the exact opposite.”

For decades the LCWR has been assimilating some of the worst elements of our postmodern culture and has been heeding the advice of those who urge it to question church teaching and to cloak its dissent behind a cryptic doublespeak. For the sake of Christ’s kingdom, may the LCWR have the courage to follow Chesterton’s lead: listen respectfully but then go do the exact opposite.

The views expressed by the authors and editorial staff are not necessarily the views of

Sophia Institute, Holy Spirit College, or the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts.

Sophia Institute, Holy Spirit College, or the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts.

Print this | Share this

By Frank W. Hermann

Frank W. Hermann is an associate professor of English at Franciscan University of Steubenville, where he teaches writing and rhetoric.

No comments:

Post a Comment