by Anthony Esolen

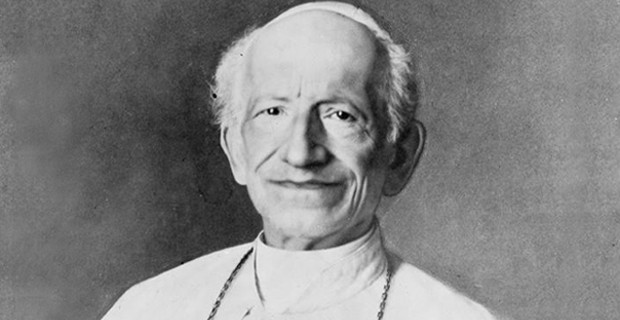

It is generally held that Catholic Social Teaching begins with Pope Leo XIII’s masterly encyclical, Rerum Novarum (1891). That, as I’ve tried to show, is a dreadful mistake. Pope Leo considered it his duty to apply to current concerns the constant teaching of the Church and of the word of God. Like Thomas Aquinas, the study of whose works he promoted vigorously, he would have considered “originality” a vice, not a virtue.

Perhaps we are misled by the title, Rerum Novarum. In our anti-society of rapacious consumption of the “new” and “improved,” and the unease instilled in us by mass marketers and politicians who cry that if we do not act now we will be lost—“Awake, arise, or be forever fall’n!” cries the Prince of Politicians to his fellow devils in Milton’s hell—we are apt to credit Pope Leo with seeing the light of novelty. No such thing. The ancient Romans held the political innovator to be a plague. Res novameans revolution, and the “spirit of revolutionary change,” rerum novarum spiritus, writes Leo, has been disturbing the nations of the world.

What are the elements of this upheaval? Leo names five: “The vast expansion of industrial pursuits and the marvelous discoveries of science; the changed relations between masters and workmen; the enormous fortunes of some few individuals, and the utter poverty of the masses; the increased self-reliance and closer mutual combination of the working classes; the prevailing moral degeneracy.” The first is a neutral datum; it is the stage. The next three are social conditions with deep moral implications. The fifth is a moral sickness which would, unchecked, vitiate any attempt to solve the problems of the working classes by monetary or juridical means—we might say, by mechanical means.

What are the elements of this upheaval? Leo names five: “The vast expansion of industrial pursuits and the marvelous discoveries of science; the changed relations between masters and workmen; the enormous fortunes of some few individuals, and the utter poverty of the masses; the increased self-reliance and closer mutual combination of the working classes; the prevailing moral degeneracy.” The first is a neutral datum; it is the stage. The next three are social conditions with deep moral implications. The fifth is a moral sickness which would, unchecked, vitiate any attempt to solve the problems of the working classes by monetary or juridical means—we might say, by mechanical means.How did matters come to this pass? Leo blames the secularism spreading like a contagion from one European nation to the next. He had made that charge in his earlier encyclicals. One after another, the institutions that once brought master and workman together have been weakened or destroyed. The guilds were abolished; Leo will, in his practical recommendations, return again and again to the model of the guild. For the guilds, founded in the Middle Ages, were social, economic, and religious all at once. Guildsmen trained the young in their trades; they maintained a high standard of quality; they provided stability in costs and profit; they cared for their invalid members and their widows and orphans; and they united in the worship of God, especially to celebrate their patronal feasts.

The abolition of the guilds, then, was of a piece with laws that “set aside the ancient religion,” leaving nothing between worker and master: “Hence by degrees it has come to pass that workingmen have been surrendered, all isolated and helpless, to the hard-heartedness of employers and the greed of unchecked competition.” Matters are made all the worse by “rapacious usury, which, although more than once condemned by the Church, is nevertheless, under a different guise, but with the like injustice, still practiced by covetous and grasping men.” I’m not qualified to comment on the Church’s monetary realism, and the difference she sees between usury and, say, the profit a passive member derives from a joint stock corporation, or the fair price one may charge for opportunities forgone when one lends money to another. What I want to note is that for Leo, since we are talking about human beings made by God and for God, the misery we cause one another cannot be cordoned off into compartments, one religious and one secular. Rapacity is a moral issue. The denigration of the Church is a moral issue. We are talking about sin.

Now one cannot cure sin by sin. Our Lord tells us: one cannot cast out devils in the name of Beelzebub. But this, Leo sees, is what some revolutionaries pretend to do: “To remedy these wrongs the Socialists, working on the poor man’s envy of the rich, are striving to do away with private property, and contend that individual possessions should become the common property of all, to be administered by the State or by municipal bodies” (emphasis mine). Leo does not condemn Socialism for its practical failure, although he notes—did he board a time-machine to visit Russia and Cuba and what used to be Great Britain?—that “the workingman himself would be among the first to suffer.” We must see the relationship aright. Socialism is not evil because it fails. It fails, because it is evil. Nor is it justified because unchecked rapacity is evil—the antisocial money-squeezing which Dickens, alike suspicious of socialists, condemned. One does not hire Belial to fight Beelzebub.

At this point, one might expect Leo to launch into economic analysis, and provide a “solution” to the trouble. But we must clear away the childishly bad thinking to which we have grown accustomed—our fetish for numbers. Man is a moral being to the core. Man is oriented by his nature toward God, with every breath he takes. We seek not money. We seek joy. A life of material comforts and moral indifference is unworthy of man; if the beasts could feel shame, they would be ashamed of that.

Instead the Pope returns to the nature of man. We work; we exercise our minds, as God commanded us even before the fall. Man puts himself into his work, and so the reward of his work becomes his own, not the property of the State. Nor is this property held at the allowance of the State, reverting to the State at his decease. For, unlike the beasts, he dwells as it were above the current of time: “Man, fathoming by the faculty of reason matters without number, and linking the future with the present, becoming, furthermore, by taking enlightened forethought, master of his on acts, guides his ways under the eternal law and the power of God, whose providence governs all things.” His deeds, says Leo, “do not die out.” He makes his own “that portion of nature’s field which he cultivates—that portion on which he leaves, as it were, the impress of his individuality.” That includes the land itself.

Thus the right of private property is grounded, not in practical economics, but in the theomorphic nature of man. Are we now ready to consider the State, and laws established for the common good? By no means. It’s a symptom of our secular disease that we idolize the untrammeled individual, motivated by one hedonism or another, whether of rapacity or lust, and the State established to adjudicate among the hedonists. Such a man is less than fully human, and such a State is at once greater than a true state, as a tumor outgrows the organ it supplants, and less than a state, in that it provides at best for a tolerably managed common-evil.

No, we must still consider what man is, but now, man as a social being. He is made for love. In particular, he is made for that God-created society, the family. Unchecked avarice may destroy families by depriving them of the material goods to which the workman rightly lays claim. But socialism destroys families by denying their very nature, and by usurping their functions: “The contention, then, that the civil government should at its option intrude into and exercise intimate control over the family and the household, is a great and pernicious error.”

Rapacity for wealth is not cured by rapacity for power. These things, then, are grave violations of Catholic Social Teaching: To proceed as if the child were the ward of the State; to seize from parents the oversight of their children’s education; to intrude the law into the family circle except when that circle has been broken by serious crime; to enact laws that encourage the dissolution of families; to enact laws that discourage the formation of families; to pretend that the basic definition of the family is the prerogative of individuals or the State; to treat monetary issues solely as between an individual and an individual, or an individual and the State, without regard to the family; to seize property from the family at the decease of its head; to relegate religion to the private sphere, so that the State, or the wealthy, or whatever aggregate may wield power, need not concern themselves with it.

More to come.

The views expressed by the authors and editorial staff are not necessarily the views of

Sophia Institute, Holy Spirit College, or the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts.

By Anthony Esolen

Professor Esolen teaches Renaissance English Literature and the Development of Western Civilization at Providence College. A senior editor for Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, he writes regularly for Touchstone, First Things, Catholic World Report, Magnificat, This Rock, and Latin Mass. His most recent books are The Politically Incorrect Guide to Western Civilization (Regnery Press, 2008); Ironies of Faith (ISI Press, 2007); and Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child (ISI Press, 2010). Professor Esolen is the translator of Dante.

No comments:

Post a Comment