Marianne Karsh was a forester until she began to see trees as more than just timber, MICHAEL VALPY writes. Now the daughter of one of Canada's foremost photographers teaches others to listen to the voices in nature

By MICHAEL VALPY

Wednesday, December 27, 2000 Posted at 9:58 AM EDT

"A spiritual discipline is designed to release control of the ego so that "the light behind the mind" can come into focus. This is the silence of the ages that gives us rest. This is where we meet God."

Rev. Lauren Artress, Grace Cathedral, San Francisco

On a sparkling, sunny day, Marianne Karsh leads a group out the door of a Franciscan spiritual retreat in the Caledon Hills north of Toronto.

Gesturing to the picture-postcard meadows, the woods, a stream, a pond enclosed by willows, she tells them: "Go and find your home." Which they set off to do, disappearing down trails, vanishing into the trees, climbing hills.

Ms. Karsh, a trained forester, is conducting a workshop on the spirituality of Creation. She believes that trees are creatures that, within the limits of their treeness, have will, volition and selfhood.

It is her purpose to summon from the unconscious -- from the souls, from the "light behind the minds" -- of her workshop participants those very ancient, archetypal, spiritual relationships humans have with nature.

Relationships that have become silted over through the past 250 years of Enlightenment rational thought, but not erased.

One of the desires in humanity's collective unconscious is the search for home, recognized by psychologists and theologians alike. It is the great metaphor for safety, rest, peace.

By instructing workshop participants to go into the countryside to find a place where they would like to live, Ms. Karsh is not only reconnecting them to nature but also reconnecting them to the sacred archetypes of the spirit.

Or, put another way, she is reconciling them with the larger mind of the universe, of which the individual human mind is a subsystem. Ms. Karsh, among many, would call the larger mind the immanent and transcendent God.

Ignatius Jesuit Centre, Guelph

Ignatius Jesuit Centre, Guelph

While working as a federal government forester in Newfoundland in the 1980s, Ms. Karsh began conducting spiritual-nourishment-in-nature workshops at the invitation of the provincial recreation department. The first courses were primarily for women, helping them to acquire self-confidence by teaching them to be comfortable in nature and about the feminineness of Creation.

Ms. Karsh, in the process, discovered a new career.

She eventually left forestry and moved to Toronto, created her own company, Arborvitae, and now conducts workshops and retreats full-time for theologians, students and anyone interested in the connection between nature and spirituality.

She leads groups into Ontario's woods to meditate, to be silent, to meet (among other creatures) wolves.

She presents slide shows on spirituality in nature. Ms. Karsh -- the daughter and niece, respectively, of renowned photographers Malak and Yousuf Karsh -- has photographed places that, to her, match descriptions of the biblical gardens of God's promise (Ezekial's creational harmony and Isaiah's wilderness vision, among others).

She conducts ecological prayer workshops following the mysticism of 12th-century theologian and physician Hildegard of Bingen, who described spirituality as the greening power of God -- the task of humans to be to flower, to come into full bloom, before their time comes to an end.

St. Hildebard of Bingen, Pray For Us

St. Hildebard of Bingen, Pray For Us

What may be most intriguing about Ms. Karsh is the paper she cowrote four years ago with Toronto theologians Nik Ansell and Brian Walsh: Trees, Forestry and the Responsiveness of Creation.

In that paper, she sets down her thinking that trees have intentional selfhood.

In so doing, she takes Creation spirituality -- for some skeptics, positioned a little too far inside the dilettante stockade of New Age-ism -- along rather an unblazed path.

Ms. Karsh and her co-authors begin with the contention that Creation has been silenced by aggressive human anthropocentrism -- humanity's arrogance that it holds mastery of the universe -- resulting in what theologian Thomas Berry has called cultural autism: humanity's lost capability to "hear" Creation.

(In today's spirituality, the theme of "hearing" and "listening" is a constant. Increasing numbers of theologians define prayer as listening for God -- emptying the chattering mind of thought so that, in the silence, the immanent God in the mind-below-the-mind may be heard.

Archetypal psychologists talk of emptying the mind of Enlightenment and patriarchal deity ideologies so that the older, warmer, ecological-harmony narratives of the Goddess, the generic feminine deity, Creation's Earth Mother, can be heard.)

The paper asks: "Can we listen to trees, and through new paradigms in forestry and tree biology facilitate such a listening?"

The answer, it says, is not a given, because "by construing nature as deaf and dumb, we have made ourselves deaf and dumb in relation to nature."

The paper then takes off on a wonderful excursion into Jewish and Christian scriptures, in which trees are variously portrayed as groaning, singing for joy and clapping their hands.

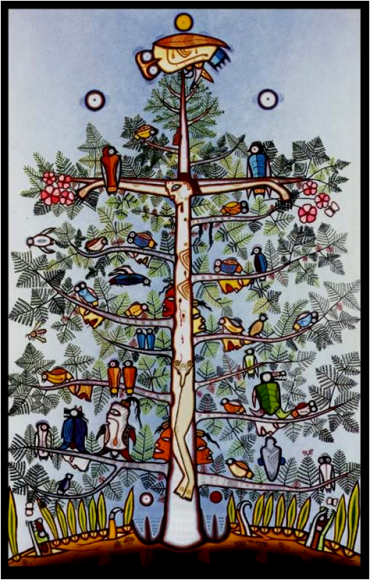

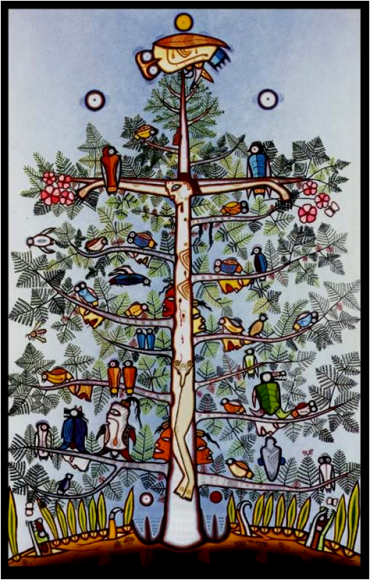

Chapel Sanctuary's "Crucifix" at Jesuit's Anishinabe Spiritual Centre in Espanola

Chapel Sanctuary's "Crucifix" at Jesuit's Anishinabe Spiritual Centre in Espanola

"We suggest that [these] metaphors are appropriate . . . if they are disclosing real dimensions of these creatures . . . [and] trees do, in fact, in their own fashion, respond to their Creator both with deep groans of longing and pain and with songs of praise."

At which point, Ms. Karsh gets into biology:

Trees, she says, are responsive creatures who display a high level of co-operation with other life forms, going beyond what is necessary or expected.

She cites the association between trees and funguses. Trees and funguses can live without one another. The association appears to be optional -- not every group of trees does it. And the sole purpose appears to be only to better each other's growth. Funguses assist trees in absorbing nitrogen and the trees feed funguses surplus carbohydrates.

Ms. Karsh says this indicates responsiveness on the trees' part, "perhaps even . . . will."

She says trees display a remarkable ability to survive and adapt in impossible circumstances. In cities, they survive intense noise, vibration, pollution and high dosages of salt.

Arboriculturalists are beginning to believe they have been wrongfully pruning trees for about as long as arboriculture has existed -- imposing treatment that causes the tree's defence system to break down, something akin to creating tree AIDS. "Yet the trees have adapted even to this mistreatment. Could it be that trees have a type of intentionality that we have previously not discerned?" the paper says.

Trees display qualities that are totally inexplicable "if considered solely from a mechanistic, non-responsive viewpoint."

Ms. Karsh says foresters cannot predict tree growth although the trees may be of the same species in the same soil, are in similar climate with the same spacing conditions, and have the same stimuli.

She suggests that this may be because trees possess a selfhood.

Forestry of the future should be characterized by a relationship of listening and communion with trees, she says.

"Neither a naive preservationism nor a distanced objective management, it will be a stewardship of care that attends to trees in all their rich and nuanced diversity, variability and individuality."

Ms. Karsh says trees affirm life. She writes about conifer trees growing in intense acid-rain conditions on fog-covered German mountains, producing a huge cone-crop in their last year of life.

"There is no apparent biological reason for this except that a cone crop ensures that a seed source will survive in case conditions get better. . . .

"Further, it takes a special channelling of energy within the tree to grow a reproductive structure. In these areas where concentrated acid mists and fogs cover trees for most of the growing season, every last ounce of the tree's last bit of energy goes into producing a cone crop.

"Why? In these conditions, a cone crop would seem to be a wasteful use of the tree's energy. However, . . . nature is not wasteful. Perhaps the cone crop is a sign of hope. In symbolic terms, this tree behaviour says: 'We believe in God's redemptive covenant, do you?' "

Ms. Karsh notes that some trees do not produce a final cone crop and die rather quickly. Perhaps, she says, they did not have the will to live. "It remains to be explained why trees under similar acidic conditions respond differently."

She writes about the 19th-century Scottish-American naturalist and conservationist John Muir, who sat beside an unfamiliar plant for a minute a day to hear what it had to say. He said: "I could distinctly hear the varying tones of individual trees . . . singing its own song and making its own particular gestures."

Ms. Karsh writes about Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock, a biologist who views the corn plant as "a unique individual," "a mysterious other," "a kindred subject," "distant, perhaps very distant cousins: strange but lovable kin."

Ms. Karsh's paper concludes by saying that "our claim that trees are responsive creatures who have things to say to us is not, at its foundation, scientific."

Rather it belongs to the prescientific world, the ancient narratives of life, to humanity's collective unconscious, to science philosopher Michael Polanyi's concept of "tacit knowledge" -- that which has always been known.

"To say, as the Bible does, that trees praise, sing, clap and rejoice is to say that trees, as trees, in their whole physical, chemical, spatial, biotic functioning can fully respond to their Creator when that functioning is uninhibited and free," the paper says.

It is a nice thought: trees clapping hands, rather than trees as mere timber.

Relationships that have become silted over through the past 250 years of Enlightenment rational thought, but not erased.

One of the desires in humanity's collective unconscious is the search for home, recognized by psychologists and theologians alike. It is the great metaphor for safety, rest, peace.

By instructing workshop participants to go into the countryside to find a place where they would like to live, Ms. Karsh is not only reconnecting them to nature but also reconnecting them to the sacred archetypes of the spirit.

Or, put another way, she is reconciling them with the larger mind of the universe, of which the individual human mind is a subsystem. Ms. Karsh, among many, would call the larger mind the immanent and transcendent God.

While working as a federal government forester in Newfoundland in the 1980s, Ms. Karsh began conducting spiritual-nourishment-in-nature workshops at the invitation of the provincial recreation department. The first courses were primarily for women, helping them to acquire self-confidence by teaching them to be comfortable in nature and about the feminineness of Creation.

Ms. Karsh, in the process, discovered a new career.

She eventually left forestry and moved to Toronto, created her own company, Arborvitae, and now conducts workshops and retreats full-time for theologians, students and anyone interested in the connection between nature and spirituality.

She leads groups into Ontario's woods to meditate, to be silent, to meet (among other creatures) wolves.

She presents slide shows on spirituality in nature. Ms. Karsh -- the daughter and niece, respectively, of renowned photographers Malak and Yousuf Karsh -- has photographed places that, to her, match descriptions of the biblical gardens of God's promise (Ezekial's creational harmony and Isaiah's wilderness vision, among others).

She conducts ecological prayer workshops following the mysticism of 12th-century theologian and physician Hildegard of Bingen, who described spirituality as the greening power of God -- the task of humans to be to flower, to come into full bloom, before their time comes to an end.

What may be most intriguing about Ms. Karsh is the paper she cowrote four years ago with Toronto theologians Nik Ansell and Brian Walsh: Trees, Forestry and the Responsiveness of Creation.

In that paper, she sets down her thinking that trees have intentional selfhood.

In so doing, she takes Creation spirituality -- for some skeptics, positioned a little too far inside the dilettante stockade of New Age-ism -- along rather an unblazed path.

Ms. Karsh and her co-authors begin with the contention that Creation has been silenced by aggressive human anthropocentrism -- humanity's arrogance that it holds mastery of the universe -- resulting in what theologian Thomas Berry has called cultural autism: humanity's lost capability to "hear" Creation.

(In today's spirituality, the theme of "hearing" and "listening" is a constant. Increasing numbers of theologians define prayer as listening for God -- emptying the chattering mind of thought so that, in the silence, the immanent God in the mind-below-the-mind may be heard.

Archetypal psychologists talk of emptying the mind of Enlightenment and patriarchal deity ideologies so that the older, warmer, ecological-harmony narratives of the Goddess, the generic feminine deity, Creation's Earth Mother, can be heard.)

The paper asks: "Can we listen to trees, and through new paradigms in forestry and tree biology facilitate such a listening?"

The answer, it says, is not a given, because "by construing nature as deaf and dumb, we have made ourselves deaf and dumb in relation to nature."

The paper then takes off on a wonderful excursion into Jewish and Christian scriptures, in which trees are variously portrayed as groaning, singing for joy and clapping their hands.

"We suggest that [these] metaphors are appropriate . . . if they are disclosing real dimensions of these creatures . . . [and] trees do, in fact, in their own fashion, respond to their Creator both with deep groans of longing and pain and with songs of praise."

At which point, Ms. Karsh gets into biology:

Trees, she says, are responsive creatures who display a high level of co-operation with other life forms, going beyond what is necessary or expected.

She cites the association between trees and funguses. Trees and funguses can live without one another. The association appears to be optional -- not every group of trees does it. And the sole purpose appears to be only to better each other's growth. Funguses assist trees in absorbing nitrogen and the trees feed funguses surplus carbohydrates.

Ms. Karsh says this indicates responsiveness on the trees' part, "perhaps even . . . will."

She says trees display a remarkable ability to survive and adapt in impossible circumstances. In cities, they survive intense noise, vibration, pollution and high dosages of salt.

Arboriculturalists are beginning to believe they have been wrongfully pruning trees for about as long as arboriculture has existed -- imposing treatment that causes the tree's defence system to break down, something akin to creating tree AIDS. "Yet the trees have adapted even to this mistreatment. Could it be that trees have a type of intentionality that we have previously not discerned?" the paper says.

Trees display qualities that are totally inexplicable "if considered solely from a mechanistic, non-responsive viewpoint."

Ms. Karsh says foresters cannot predict tree growth although the trees may be of the same species in the same soil, are in similar climate with the same spacing conditions, and have the same stimuli.

She suggests that this may be because trees possess a selfhood.

Forestry of the future should be characterized by a relationship of listening and communion with trees, she says.

"Neither a naive preservationism nor a distanced objective management, it will be a stewardship of care that attends to trees in all their rich and nuanced diversity, variability and individuality."

Ms. Karsh says trees affirm life. She writes about conifer trees growing in intense acid-rain conditions on fog-covered German mountains, producing a huge cone-crop in their last year of life.

"There is no apparent biological reason for this except that a cone crop ensures that a seed source will survive in case conditions get better. . . .

"Further, it takes a special channelling of energy within the tree to grow a reproductive structure. In these areas where concentrated acid mists and fogs cover trees for most of the growing season, every last ounce of the tree's last bit of energy goes into producing a cone crop.

"Why? In these conditions, a cone crop would seem to be a wasteful use of the tree's energy. However, . . . nature is not wasteful. Perhaps the cone crop is a sign of hope. In symbolic terms, this tree behaviour says: 'We believe in God's redemptive covenant, do you?' "

Ms. Karsh notes that some trees do not produce a final cone crop and die rather quickly. Perhaps, she says, they did not have the will to live. "It remains to be explained why trees under similar acidic conditions respond differently."

She writes about the 19th-century Scottish-American naturalist and conservationist John Muir, who sat beside an unfamiliar plant for a minute a day to hear what it had to say. He said: "I could distinctly hear the varying tones of individual trees . . . singing its own song and making its own particular gestures."

Ms. Karsh writes about Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock, a biologist who views the corn plant as "a unique individual," "a mysterious other," "a kindred subject," "distant, perhaps very distant cousins: strange but lovable kin."

Ms. Karsh's paper concludes by saying that "our claim that trees are responsive creatures who have things to say to us is not, at its foundation, scientific."

Rather it belongs to the prescientific world, the ancient narratives of life, to humanity's collective unconscious, to science philosopher Michael Polanyi's concept of "tacit knowledge" -- that which has always been known.

"To say, as the Bible does, that trees praise, sing, clap and rejoice is to say that trees, as trees, in their whole physical, chemical, spatial, biotic functioning can fully respond to their Creator when that functioning is uninhibited and free," the paper says.

It is a nice thought: trees clapping hands, rather than trees as mere timber.

No comments:

Post a Comment